Darjeeling, best known for its misty slopes and breathtaking views of the Himalayas, isn’t quite the same anymore. Much is brewing, and no, it is not the teas it is famed for.

In May 2021, the West Bengal government announced it would be introducing Bengali as a compulsory language to be taught in all schools across the state. That was, for the many living in the hills, a slight too many and almost simultaneously one that led to widespread protests, beginning with black flag demonstrations at the Chief Minister’s visit on June 5, further spiraling into burning of vehicles and throwing stones at the police and paramilitary personnel that have since resulted in the deaths of eight civilians.

A call for a strike, complete shutdown of one and all establishments that include schools and banks, not to mention the hotel and tea industries, in the peak of tourist season and the second flush, has been ongoing since then, today, July 27, being the 43rd day. Almost immediately, the state government in swift measure blocked all internet and cable television services and deployed large flanks of the paramilitary forces in the region.

For those unfamiliar as to why the introduction of a language would spill over into such a prolonged agitation, a little background as to the history of Darjeeling and its role in the state of West Bengal.

West Bengal is the state that lies extreme to the east of the Indian sub-peninsula, the rest of the seven northeastern states separated by the country of Bangladesh. The only route to and from the northeastern states is through the town of Siliguri that lies in the foothills of the Darjeeling district.

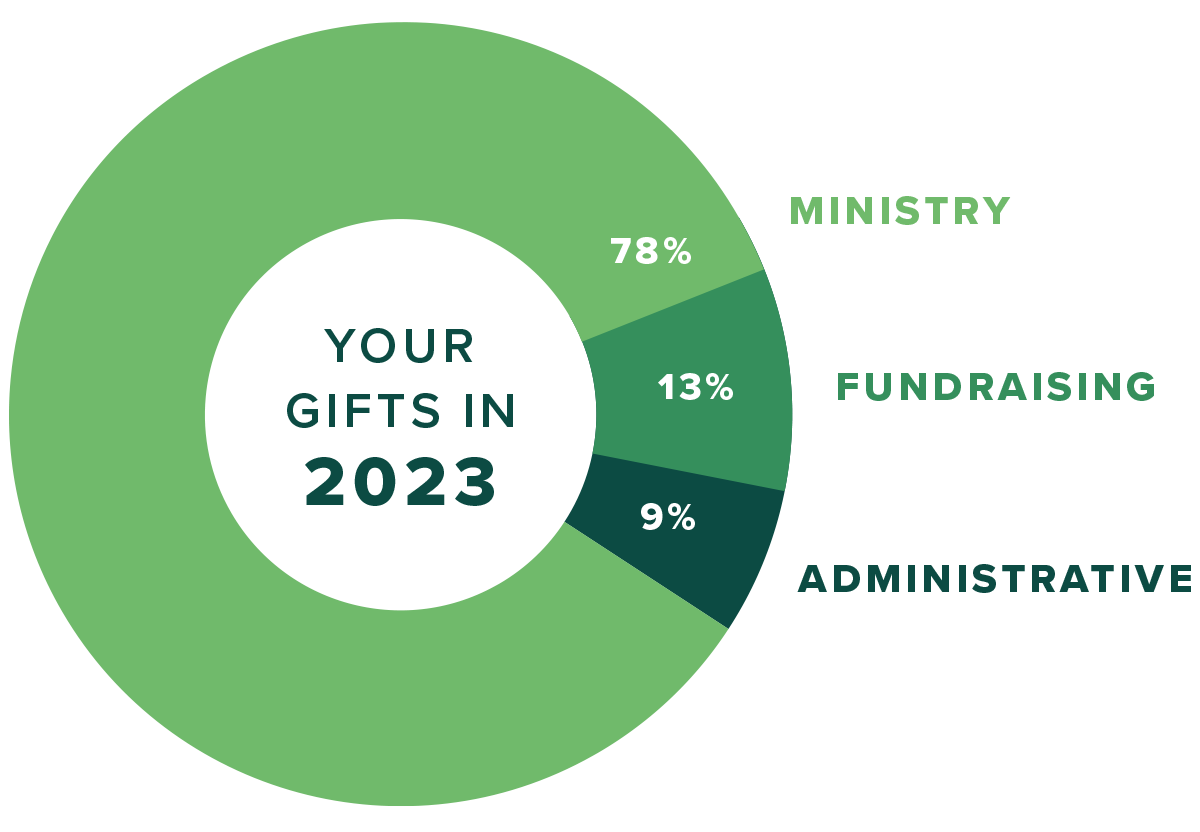

OneChild works in India, which includes the state of West Bengal, serving kids in poverty and providing physical, spiritual and emotional relief to families in need. OneChild is committed to helping children in poverty in remote places, no matter how difficult.

So, what is so important about Darjeeling? The fact that it lies just above what is known as the “Chicken Neck,” a 20-kilometer- wide corridor that includes the town of Siliguri and one that connects these seven northeastern states to the rest of the country.

These seven states as can be seen in the map here share their borders with China, Myanmar, and Bangladesh, and almost all these states have had their share of bloodshed, some in the carving of its statehoods and some unfortunately, still. Hope has been in short supply.

As far as the history and ethos of Darjeeling itself, its people, language, and culture are completely different from that of the rest of the populace that fills the state of West Bengal. In fact, it did not even belong to West Bengal, rather the kingdom of Sikkim, whose ruler, the Chogyal, waged several wars against the Gurkhas of Nepal who had made several attempts to conquer the region from him. A resulting defeat in 1814 led to the eventual signing of the Sugauli Treaty wherein Nepal had to include the territories which the Gurkhas had annexed from the Chogyal to the British East India Company as well.

Later after the independence of India in 1947, Darjeeling was merged with the state of West Bengal. A separate district of Darjeeling was established consisting of the hill towns of Darjeeling, Kurseong, Kalimpong, and some parts of the Terai region. Since then and spurred on the by creation of Sikkim as a state in 1975, there has been a rising clamor for a separate identity, an autonomous state and the recognition of Nepali as an official language.

While the latter has been acknowledged, with the Nepali language listed in the Eighth Schedule to the Constitution of India as an Indian language having an official status in 1961, the demand for a separate state has been ongoing.

For the most part, Gurkhas are a soft-spoken lot, warm and generous, exhibiting a fierce loyalty, a trait well served in the various Gurkha regiments across the world. Unfortunately, for the rest of the country, Gurkhas have often been portrayed and widely accepted as the bungling idiots who slur the Hindi vocals and more often than not, are deemed fit to be just the local guard at the door, the chowkidar, a depiction that is understandably most resented.

Over the years, as with other territories’ voices for a separate statehood, the protests, while ongoing, really had no representation and for the state and capital, Delhi, it was generally perceived that the cause as such would die a natural death. That is until 1980.

Subhas Ghising, an ex-soldier and former teacher had been quite vocal in the demand for statehood since the 70s, but it was only in 1980 that the GNLF was born and a formal statement for the issuance of a separate statehood, Gorkhaland presented. In the next few years that were to follow, peaking at 1986-87, the party led by him set this quiet town and the surrounding hills on fire, literally.

It was not uncommon in those days to see smoke spiraling in the distance or hear of veiled threats of decapitation should anyone protest. The whole region locked down, across markets, schools, and hotels as violent protests began. The governments, both state and central, moved in brutal force to quell this, the worst being July 27, 1986, where 13 protesters who were burning copies of the India-Nepal Friendship Treaty, died in a GNLF rally in Kalimpong when police opened fire.

After many such bloodied encounters and long consultations, both the state and central governments then negotiated on granting a semi-autonomous administrative body to the Darjeeling hill region. In July 1988, the GNLF gave up its demand for a separate state, and by August 1988, the Darjeeling Gorkha Hill Council came into being, with Subhas Ghising as Chairman who by then won the first council elections.

However, the path since then has rocky at best. While the GNLF continued to rule and win over consecutive council elections spanning two decades, progress otherwise in the hills remained at a standstill.

The region still continues to remain the same with no or very little civic development in terms of roads, electric, and water supplies, not to mention medical facilities or the provisions for higher education. There were widespread allegations of corruption across the board that the DGHC and its members were too busy lining their pockets from the state funds, with very little actually being used for the betterment of its people.

And although in a stunning coup led by Ghising’s right-hand man, Bimal Gurung, the GNLF were soon ousted and a new party in place, the GJM, Gorkha Janmukti Morcha, matters and overall development otherwise, remains at status quo. Any voices of dissent or otherwise have been dealt with viciousness as in the cold-blooded murder of Madan Tamang on a busy street in 2010, while the primary suspect, Bimal Gurung, continues to walk the same streets, a free man.

These recent clashes and the outpouring of people across the nation and even the world has very little to do with the party ideology, although different factions across the board may speak the same language of Gorkhaland. This time the massive support seen online and in street demonstrations are but the singular cry of a people that have had enough.

Enough of the politics of those whom they had seen as a leader, enough of the forced imposition of a language that has never been theirs to begin with and enough of living a life marred with labels, missed opportunities, and misplaced priorities.

Along with the rising cry of Ayo Gorkhali (here come the Gurkhas) is also the term across almost every social media post, that of #NotMyLeader. However, as clichéd as it sounds, unfortunately, out of sight is out of mind. For Darjeeling and its surrounding towns, all tucked away in the hills, the plight of the common man is something that can never be felt in the bustle of its capital city, Kolkata, or even among the seats of power in Delhi.

For most Indians, Gurkhas are foreigners, as harsh as it sounds. Like them, and the rest of the Northeast population, they do not look anywhere close to the average Indian; and furthermore, they do not sound, dress, eat, or talk the way most Indians do. There could be no further distance, both geographically and otherwise, between the them and us.

So, while the clamor grows and while the hills remain blanketed under troops and the shutdown, someone really does need to step up to the plate. Whether it is the collective band of new and old factions, or the state and central government representatives is irrelevant. If it is indeed the peoples’ best interests that they seek, then gather they must.

Or else climb every mountain would seem an insurmountable task, a line best sung at school plays. No amount of agitation or strikes, while good publicity, would ever bring that about. In the end it would all just amount to a storm in a teacup and going by the days passing by, perhaps not even that after all. Storm yes, tea definitely not.

Read more about our work in India.

Read about how a Hope Center’s intervention brings healing to a young girl in India.