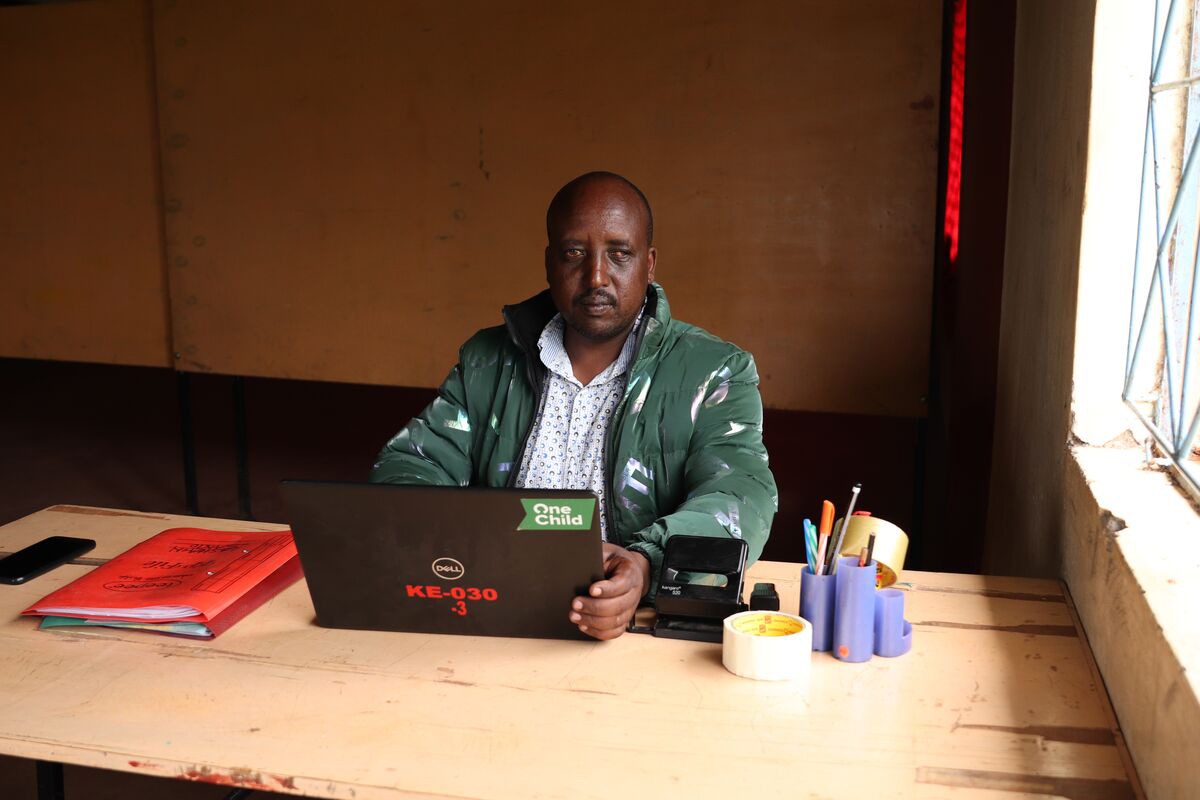

His Hard Past Helps Him Shape Kids’ Bright Futures

Story and photos by Donna Atola, Kenya Field Communications Specialist

Shadrack, a Child Champion in Kenya, knows how it feels when poverty gets in the way of plans. Now he draws on his difficult experiences to help young people in his community pursue their dreams.

Children and parents in Kajiado, Kenya, know what to do when they need advice: They ask their Hope Center’s Child Champion. This champion has wisely helped families navigate difficult situations for years.

Shadrack, a Child Champion at Emarti Hope Center since 2020, has served children for over 13 years at various centers, previously as a teacher and volunteer.

The current role is perfect for Shadrack, even if it’s a little different from the schoolteacher job he dreamed of as a child. While challenges of poverty and family dynamics kept him from pursuing that path, he’s glad he eventually found a way to serve children in his community.

Now he uses lessons learned from his difficult years as a young adult to guide kids and their parents at his Hope Center.

A Maasai Childhood

Maasai women singing during a celebration

Shadrack was born into a large family. His father had three wives, which their Maasai culture allows.

Shadrack recalls growing up in a home full of joy and love. His parents loved him and his siblings dearly. They made sure that all 12 children in the home got an education — even though schools were not close to their home. Little Shadrack had to cover 10 miles every day to attend school.

“I left home at 5 a.m. every day so that I could be at school by 7 a.m., and left school at 5 p.m. Our parents provided us with school supplies and made sure we attended school every day,” he recalls.

During school holidays, Shadrack, being the oldest boy, herded his father’s cattle — something he enjoyed because he also got to play with friends who were herding their families’ livestock.

A Fateful Journey

Shadrack excelled in his primary school and topped both his school and his district in the final exams. This earned him a slot at a quality high school in Kajiado, where he realized he wanted to become a teacher. He looked forward to joining a teachers’ college or pursuing a bachelor’s degree in education at a university.

But poverty and nature got in the way of his dreams. When Shadrack graduated high school in 2002, a serious drought had begun to afflict his community — a drought that would last for four years. When he returned home after his final high school exam, his father gave him an important task: to help their cattle survive the drought.

A young herder in Kajiado tends the family’s valuable cattle

Instead of starting college, Shadrack had to take his father’s 78 cows in search of water and pasture. As much as he worried and dreamed about his future, he was happy to help save the cattle, the only wealth his family had.

He began walking the cows toward Thika, a distant town northeast of Nairobi. For weeks, Shadrack herded the cows under the hot sun, stopping at night to set up a makeshift tent of plastic sheets. As the slow, 100-mile journey continued, several cows died of hunger and exhaustion.

When they finally reached Thika, which is much colder than Kajiado, even more animals died because of the change of weather.

It was a difficult experience, but Shadrack says it taught him lessons he carries with him today.

“It was a very tough time, but I learned to be resilient, accountable, and I learned what being a good steward entails,” he says.

Learn about the hard life of child herders in Turkana, another region in Kenya

A Dream Deferred

The drought finally ended four years later, and Shadrack made his way home.

When his father saw that only 18 of the 78 cows had returned with Shadrack, he told his son he needed to get married. He feared that all the cows would die, leaving Shadrack with no dowry to offer a future bride.

But Shadrack didn’t want to marry. He was young and wanted to pursue his dream of becoming a teacher. His father disagreed with his son’s plan. Not only would more school cost money he didn’t have, but he wondered why Shadrack wanted to pursue higher education before getting married. To the Maasai, a firstborn son getting married shows leadership and respect for their traditions.

Seeing that his father disapproved of his choices, Shadrack fled to Nairobi to look for casual jobs that would allow him to earn an income and save for school. He got a job at a security firm, supervising security guards.

But as his economic situation improved, his strained relationship with his father continued to weigh on him. Around the same time, Shadrack began attending church. He decided to give his life to the Lord, hoping that his heavenly Father would reconcile him to his earthly father.

After being born again, he kept doubting his choice to run away from home. He also asked God a lot of questions.

“I worked and had an income. But I felt so empty. I felt like I wasn’t living to my full potential, and I asked God to guide me back to the right path. I also wanted to be on good terms with my father, who I loved so much and loved me back,” he remembers.

One day as he was praying, he heard a still voice that he believes was God asking him to go back home and reconcile with his father.

Shadrack was obedient to God’s prompting

Becoming a Child Champion

Following God’s prompting, Shadrack returned home, and his father was happy to have him back. Shadrack began volunteering at a nearby school.

His journey as a Child Champion began when his friend, a pastor named Momboshi, asked him to volunteer at a Hope Center his church had recently set up.

Life is a struggle for many children near Emarti Exodus Hope Center

After joining the Hope Center, Shadrack began to form new dreams for his future. He signed up at a theology school and studied and graduated with a diploma in theology.

That same year, he married. Today, he and his wife have four children, three girls and a boy.

Helping Kids Dream

In his role as a Child Champion, Shadrack draws from his personal experiences. He says that, like his own parents, most parents in the community struggle to allow their kids to pursue their dreams and ambitions, mostly because of culture and a lack of formal education.

He says many parents in the area also have a limited view of careers they want their children to pursue.

“It is easy for a parent to understand when a child says they want to become a doctor, teacher, nurse, a pilot, because these are good careers. … They are also thought to be more marketable than others, so they would try to stop their child if they dared to dream otherwise,” he says.

But some of those careers are possible only when a child excels in high school and goes to college. Some kids struggle academically from primary school. But most parents in Kenya insist on the child going through all the classes even so.

Like most parents in Kenya, parents in Shadrack’s community believed that the only way a child could excel in life is by going through the education system that Kenya previously had, where a child had to go through primary and secondary school to come close to being successful in the community.

That system was good, but it didn’t account for children who excelled outside of core classes, maybe in sports, creative arts and other talents. It made most kids shy away from exploring their talents and gifts.

But a new education system in the country gives flexibility for a child to excel in their talents by taking vocational classes while still studying core subjects.

Vocational skills like beadwork can provide a youth with a livelihood in the future

This is something Shadrack deeply embraces, and he has slowly begun helping such parents appreciate their kids’ talents. The Hope Center has several skills training classes. The kids are allowed to select what they would love to learn.

Apart from the training at the center, he also has conversations with the kids and helps them identify their talents and dreams while they are still in primary school. He then talks with their parents about how they can best support their kids.

He says these conversations are important because he wants parents to be part of the community that champions the kids.

“But this is impossible if we as Child Champions do it alone, because their parents spend more time with them than we do, and they have a greater impact on their lives. And this is why it is important for all of us to be on the same page,” he says.

These conversations are especially helpful once the kids join high school and some choose to pursue vocational training.

“Some children come to me when they change their minds about what they want to pursue, mostly after joining high school. They come to seek advice and even ask me to talk to their parents. This becomes easy if we already had the conversations when the child was in primary school.”

It is important for parents to listen to their kids, he says, because when they force children down a path they don’t want to take, they end up unhappy or drop out of school. When they drop out, they end up doing drugs, participating in petty crimes or mining sand from a dried riverbed to sell — which is illegal because it destroys river banks and leads to flooding when the river’s seasonal flow resumes.

Shadrack is devoted to helping kids find the right path in life

Over the years, Shadrack has helped kids pursue training at vocational schools for careers like pastry-making and baking, hospitality and hotel management, plumbing and mechanics. He believes that all children in hard places can excel if the adults in their lives listen to them and guide them in wisdom.

“No child was born to fail,” says Shadrack. “They are all destined for success because God has placed something great in them. But it takes an intentional Child Champion to help the child discover the greatness within and hold their hands to success.”

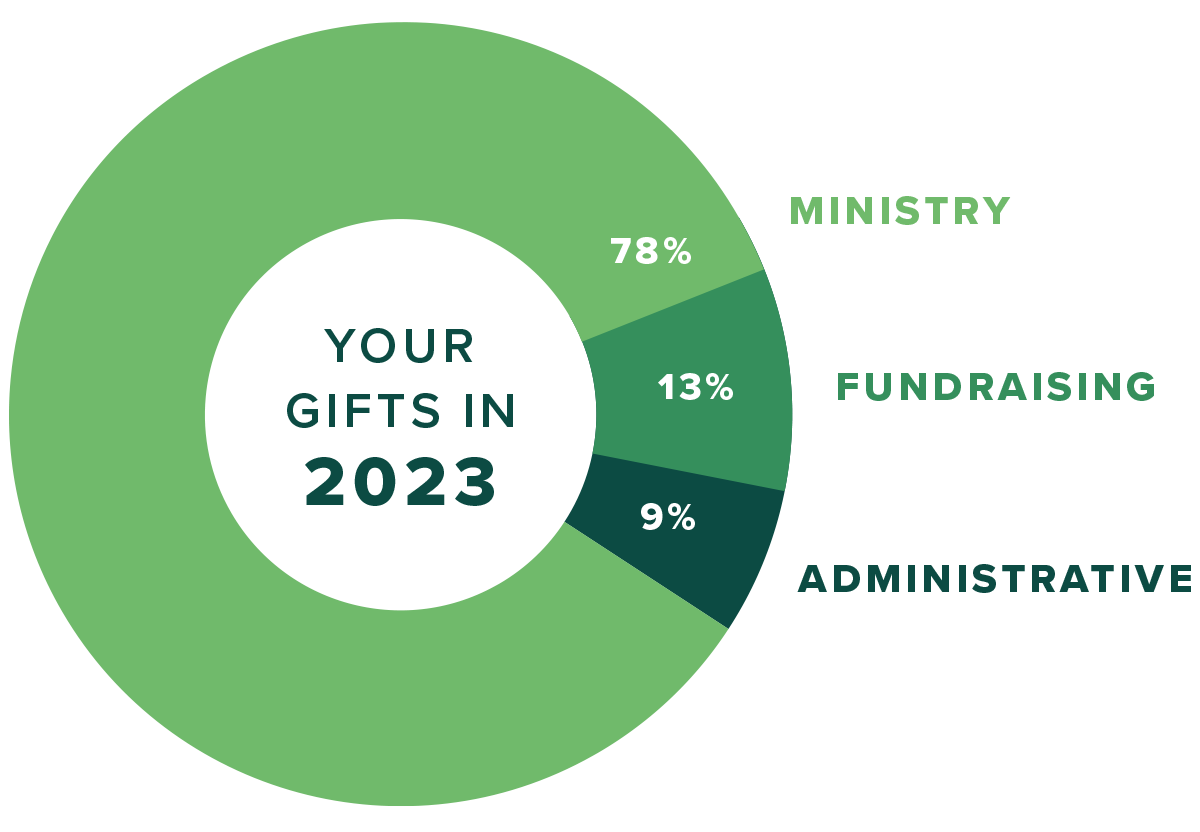

Help Launch a Hope Center

Give more kids in hard places a chance to dream and thrive with a gift to help launch a Hope Center.

Give Now