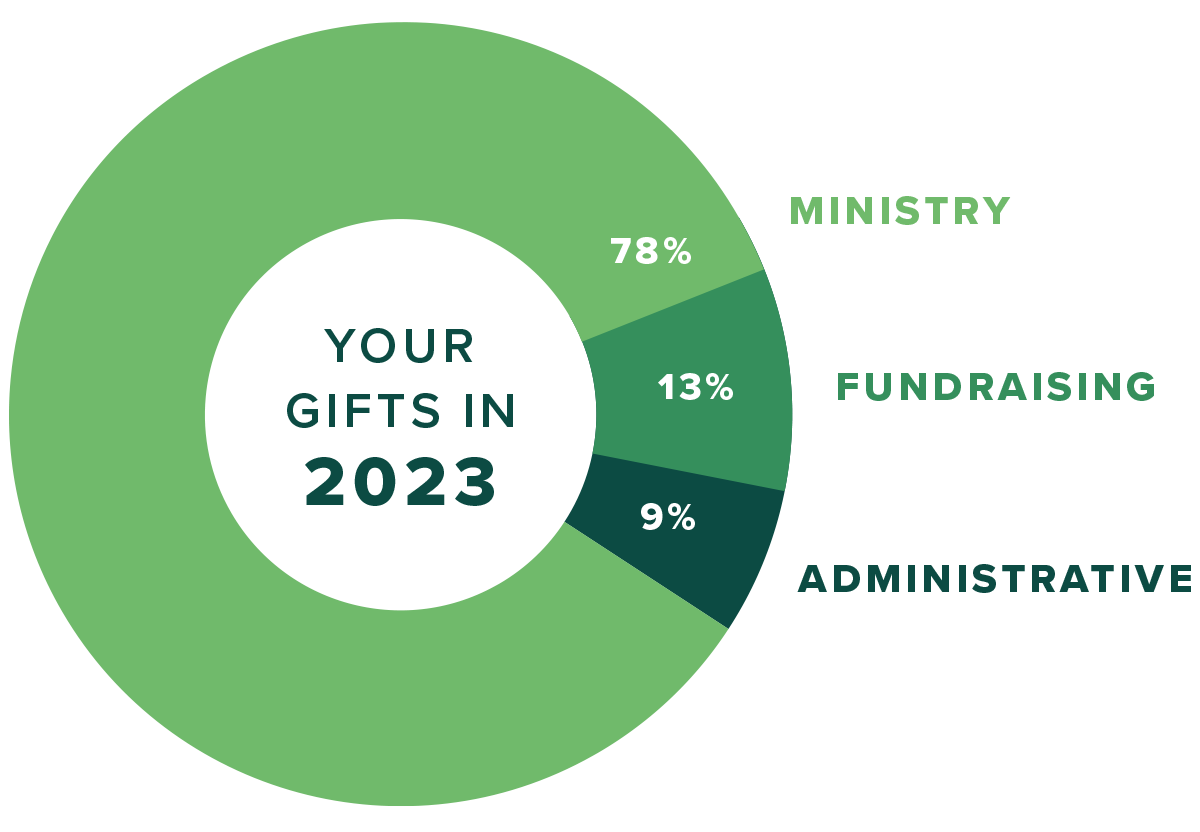

What it Costs to Feed a Family in Kenya As Food Prices Soar

By Donna Atola, Kenya Field Communications Specialist

Since 2020, more families are facing food insecurity exacerbated by inflation, extreme weather and instability. Meet four families in Kenya who share about their struggles with hunger — and their reasons to hope.

Living Day-to-Day in Nairobi

Lewis, 14, lives in a rented house in Kawangware, Nairobi, with his mom, sister, and the two cousins his mom adopted after their parents passed away.

On the table is a four-day supply of food — about 9 pounds of corn flour, 4 pounds of wheat flour, 4 pounds of sugar, 1 liter of cooking oil, and a bar of soap — all for just KSh1,000, or about $8. Five years ago, these same items cost only $5, highlighting the family’s struggle to secure daily meals.

These items are just part of what the family needs to prepare a meal every day.

Lewis with his family and a four-day supply of food

Fortunately for Lewis’ family, all the children attend a Hope Center, World Hope Academy, where they receive morning tea, including a snack, and a meal at lunchtime, only coming home for dinner.

On good days, when Lewis’ mom has sugar, she prepares tea in the morning. But it is mostly reserved for the weekends when they are away from school.

For dinner, she prepares ugali, a type of cornmeal made from corn flour that is cooked in boiling water until it reaches a doughy consistency, served alongside kale that is sauteed with onions, cooking oil and salt.

This simple dinner costs Lewis’ mom $2, yet she makes only $5 daily from working as a day laborer. Most of her work is done at the Hope Center, where she launders the football team’s jerseys. On days when the job is not available at the center, she searches for cleaning jobs in her neighborhood.

Struggling to stretch her $5 daily earnings to pay for food, rent and the kids’ other needs, she finds support from the Hope Center, which covers the children’s education.

During his visit to Lewis’ home, Gideon, a Child Champion from the Hope Center, learned that Lewis’ mother had been anxious about not having a meal that evening because she had no jobs that day. When Child Champions visit a home, they bring a food basket for the family, so his visit came at a perfect time.

“She told me that she didn’t know what they would be taking for dinner, so when I called her to inform her of the visit, her hope for a meal that evening came alive,” says Gideon.

Water for Oil in Malindi

Amani, a sponsored 11-year-old boy, joins his parents and other family members in front of their house in Malindi, a coastal town in Kenya.

On their family property, which includes two other small, earthen-walled houses, Amani lives with his 10 siblings, a sister-in-law, a nephew and his parents. Though they have separate houses, the family upholds the Swahili tradition of gathering to cook and share meals. Seated on a mat, they enjoy their time together, reinforcing the bonds of family and culture.

On the mat is a spread of food that sustains a family of 15 for a day and a half. It includes four packets of about 18 pounds of corn flour, 4 pounds of beans, 2 pounds of sugar, a packet of tea leaves and a packet of salt, all totaling around $8.

A Child Champion visits Amani’s family in 2020.

Back in 2020, with the same $8, this family could also purchase 2 liters of cooking oil. Fast-forward to today, and that essential kitchen staple is now out of reach for them. Like Amani’s family, many families have had to resort to boiling their meals, despite their preference for the delightful crispness that frying brings.

The family mainly uses corn flour to whip up porridge for breakfast, but that’s usually reserved for the little ones. The rest of the family must wait for their one main meal of the day — either lunch or dinner — each meal a testament to their resilience in trying circumstances.

For their main meals, Amani’s family relies on ugali, which they pair with either boiled beans or traditional leafy greens known as “Mchicha,” sauteed with cooking oil, onions and tomatoes — when they can afford it.

These meals often reflect a struggle, as Amani’s parents scrape by on a meager $35 a month from selling charcoal.

This income is anything but reliable; there are times when they can’t even get charcoal to sell, forcing them to search for farmhand jobs. Amani’s father, a trained plumber, also looks for plumbing jobs in the village, hoping he’ll be lucky enough to find work.

The family also practices subsistence farming, planting green grams (also called mung beans), cowpeas, cassava and millet — all entirely dependent on rain. They may harvest once a year in a good year, as this coastal region experiences long stretches of scorching heat with unpredictable rainy months.

However, the reality is stark: Most of what the parents earn goes straight to putting food on the table, leaving no resources for other basic needs, let alone unforeseen emergencies.

Thankfully, the Hope Center’s Child Champions frequently visit these families at home, bringing food baskets. Before buying groceries, the champions ask about the family’s needs. For example, when they have plenty of corn after harvest, families often request cooking oil instead.

Turkana — a Dry and Hungry Land

Pitee, 13, moved in with his grandparents after he lost his parents. Together with his aunt and cousins, his family of eight lives in Lotubae, a village in Turkana.

Pitee, in blue, with family members and three days’ worth of food

Three days’ worth of food sits on their table — about 7 pounds of sugar, 7 pounds of rice, 2 pounds of beans, a half-pound of green grams and three tea bags, totaling $8. It’s a stark contrast to 2020, when that amount of money could stretch to feed the family for five days.

Pitee and his family mostly count on one meal, dinner, because during the day, they are all busy.

When they wake up on school days, Pitee and his cousins milk a goat and drink the milk raw before running to school. However, this small pleasure comes only when the goat has recently given birth.

While the children are in school, their aunt tackles household chores, and their grandmother, Akeno, searches the bush for firewood to convert into charcoal for sale.

Pitee’s grandfather herds their five goats by the seasonal river. When the river has sufficient water, he uses irrigation to farm corn, sorghum and cowpeas, which the family eats.

Turkana is hot, arid and sandy, with temperatures ranging between 68 and 104 degrees Fahrenheit. The people of Turkana are nomadic pastoralists, or herders. But because of subsequent raids from neighboring communities, Pitee’s family, like many others, lost most of their animals, so they are forced to try irrigation farming or charcoal selling to earn a living.

On days when charcoal is selling, they earn about $4, which is only enough to buy a day’s meal. Unfortunately, the meals are never a balanced diet; they are mostly carbohydrates because corn is readily available, and things like fruits are luxuries and are hard to come by.

Such an imbalanced diet can have serious consequences. According to a report by UNICEF*, the key drivers of childhood undernutrition include disease and poor diets, especially between 6 and 23 months. This is due to food insecurity, insufficient care practices and harmful social norms.

But thanks to sponsorship, Pitee attends the Hope Center, where he receives a balanced diet.

Soaring Food Prices in Kajiado

In 2020, Natasha’s family could buy 2 liters of cooking oil for just $3. But today, that same amount only buys a single liter. This harsh reality highlights the effects of inflation.

Natasha, 14, lives with her mother, Sabina, her four brothers and two sisters in a small, rented house in Kajiado. On a typical day, Sabina would delight in cooking a variety of meals, like rice dishes, ugali, chapati (an unleavened flatbread) or githeri, a local dish in Kenya made from boiled maize and beans, all sauteed together in cooking oil, onions, tomatoes and green peppers.

But today, their table displays just enough food for three days: about 2 pounds of rice, 2 pounds of sugar, a liter of cooking oil, 9 pounds of corn flour and a packet of tea leaves — all purchased for $8.

It’s a far cry from five years ago, when the same items would have cost $3, less than half what the family is paying now. Inflation and a scarcity of job opportunities force them into a difficult situation.

Sabina works as a day laborer, washing clothes for others, where she only makes about $2 a day — if she’s lucky. Back in 2020, that amount could cover a day’s meals for the family and still let her save 20 cents toward her rent. Now, all the money goes toward providing one day’s worth of meals, yet it’s never enough.

Natasha, left, with her family and three days’ worth of food

She sometimes gets relief when Natasha’s Child Champion, Noah, visits with a food basket to get them through. They often manage just one meal a day — typically dinner and, when they can, a cup of tea in the morning.

But on Fridays, if Sabina can’t find work, Natasha still doesn’t have to worry about missing food that evening because she knows she will receive nutritious meals at her Hope Center.

The Next Meal

Unlike many kids who might wander to a stocked pantry or fridge, kids like Lewis, Amani, Pitee and Natasha face a different reality. The simple act of seeking a snack or asking their moms, “What’s for dinner?” carries a weight far beyond simple curiosity. It’s a question that is most likely met with a hesitant glance and a quiet explanation of what little food is available.

The daily rhythm of meals, so often taken for granted, is replaced with a constant negotiation of scarcity.

Even basic staples might be in short supply, and the idea of a balanced diet feels like a distant dream. Mealtimes are less about enjoyment and more about survival, a moment to stave off hunger rather than savor flavors.

For these children, the taste of chicken or beef is a rare and fleeting memory, a luxury reserved for the most special occasions. It’s not a regular part of their diet, not a source of readily available protein.

Instead, they rely on meager portions of whatever food their families can gather, their bodies constantly yearning for nourishment that is often beyond their reach.

Hope Centers Feeling the Pinch

Just like families, Hope Centers are themselves not immune to the very pressures they seek to alleviate. Rising food costs have strained their budgets, forcing them to spend more on food and at times stretch the limited resources further without compromising the quality and quantity of meals provided.

In the recent past, there has been an increase in the number of children who aren’t registered in OneChild’s program coming to the Hope Center with their registered siblings so they can get a meal. Some children in the program bring lunch boxes to store extra food so their siblings can have a bite when they get home in the evening.

With limited resources, the Child Champions have a tricky time balancing the number of unregistered children coming to the centers while still ensuring the food is sufficient for all of them. They do not have to ask the unregistered to leave because they understand the relief that a bite of food has from the hunger that gnaws at kids in hard places.

Apart from spending more on food, the champions must look for signs of malnutrition when the children undergo their annual health screenings.

But this is only possible because of the generosity of faithful sponsors and supporters, who are feeling the effects of inflation themselves. These supporters enable Child Champions to keep showing up for the kids and families, who need them now more than ever.